Squat depth is a hot topic in the world of strength training. Some coaches argue that unless you're squatting butt to floor, you're not getting all the benefits of this awesome exercise. Others say the goal is to get your quads parallel to the ground So, how low should you really be squatting?

When I first started coaching clients, I thought everyone needed to squat deep. That perspective changed after working with hundreds of different people. Some of my clients crush deep to-the-floor squats, but others struggle to squat below parallel no matter how much they practice mobility or technique.

Video of the Day

Video of the Day

Not everyone is built for super deep squatting — and that's totally fine. Each body is unique and everyone's squats look a little different. Deep squatting is a fantastic display of strength and mobility, but it's not the only way to build lower-body strength and muscle. Squatting to parallel —and for some, even a little higher — still gets you great results.

Related Reading

Deep Squats vs. Normal Squats

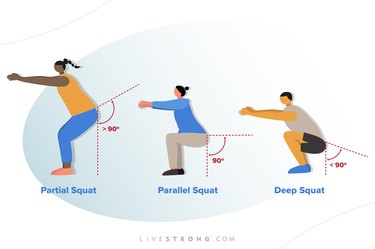

Before we dive into squat depth, let's define three general categories of squats:

- Partial or half squat: A squat where your thighs are above parallel with the ground and your knee angle is greater than 90 degrees.

- Parallel squat: Squatting to parallel means your thighs are parallel with the floor. The crease of your knees is even with or just below the crease of your hips. This is also called a 90-degree squat because your knees form a 90-degree angle in the bottom of the squat.

- Deep squat: In the bottom of a deep squat, your thighs sit below parallel and your knee angle is less than 90 degrees.

How Low Should You Squat?

Unfortunately, we're still a little uncertain if deep squatting can actually build more strength than parallel or partial squats. Most of the research around this question isn't necessarily applicable to the verage gym-goer. And many of these studies also come to conflicting conclusions.

Both partial and full squats work your quads in similar ways, according to a small June 2017 study in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. But partial back squats target more of your glutes and stabilizer muscles than the full squat.

A small September 2019 study in the European Journal of Applied Physiology found full squats may actually be more effective than half squats for developing your glutes. Clearly, there's some conflicting information here.

So, what do we know for sure? Squatting to parallel (or about an inch below) is a great place to start. Depending on your current strength and mobility, you may only be able to do a partial or half squat at first. Start at whatever depth you can achieve with proper form — heels on the floor, chest upright, back flat — and then work on squatting lower as your strength and mobility increase.

Not everyone can squat below parallel right away — or ever. Everyone's body is built differently. Plus, like anything else in fitness, you do have to be intentional and focus on this skill if you want to improve it.

If you're doing resistance training for general health benefits, reaching new squat depths may not be a priority in your routine. Doing squats to parallel is still beneficial and can help you build a basic foundation of strength in your quads and glutes.

Bottom line: Work to squat as low as you can, but don't give up on the movement if a deep bottom position isn't in the cards for you. Building strength in the range of motion available to you is much better than not squatting at all.

Related Reading

Benefits of Deep Squats

There are some great functional benefits to squatting deeper. Deep squats take your knees, hips and ankles through a larger range of motion. They build strength in more positions versus a normal squat that builds strength in a smaller, more limited range.

Deep squats also require higher levels of skill and mobility to perform safely because they put extra pressure on your knees and demand more from your core, back and legs.

And considering they require more skill and range of motion, lower squats can help prepare your body for unpredictable demands of life, according to Ross Oberlin, CPT, founder of RC Training & Fitness.

"People who can move moderate weight through full ranges of motion are often going to be more resilient than those who move heavy weights through limited ranges of motion," Oberlin says. "Someone who only exposes their body to very limited ranges of motion may have a harder time getting themselves out of weird positions unscathed."

Are You Squatting Too Deep?

Deep squats aren't always the best, though. Whenever his clients feel uncomfortable squatting, Oberlin takes a step back. Improving technique, reducing the weight and changing to an alternative squat variation can help build the strength needed to squat low.

"There's also such a thing as squatting too deep, where we lose our ability to maintain tension," Oberlin says. Whenever your heels pop off the floor, your chest faces the ground or you excessively round or arch of your back, you may be going too low. These compensations happen when you lack mobility in one or more joints or aren't yet strong enough to handle a certain depth.

Some people can't squat without pain unless they perform an above-parallel squat. This might happen as a result of past injury or general inactivity. I've had a few of these clients over the years, and our training sessions were a lot more productive and positive when I allowed clients to use a slightly reduced range of motion.

8 Factors That Affect How Deep to Squat

Many factors can affect how deep you're able to squat. Although most of these can be modified or corrected over time, a few are out of your control.

1. Limb Length

If you have long legs — especially long femurs — you may have a hard time squatting deep without compromising your form. This is because longer legs cause you to lean forward as you squat to maintain your center of gravity. Trainees with longer torsos and shorter legs usually have an easier time squatting deep and staying upright.

2. Hip Joint Shape and Size

The hip is a ball and socket joint that comes in a variety of shapes and sizes. Some people's hips allow for smooth deep squats. For other folks, squatting to or below parallel is painful or downright impossible because they don't have enough room in their hips. These skeletal differences are normal, and there's nothing you can do about them.

3. Injury History

Past injuries and surgeries can permanently affect your body and may change the way you move. This doesn't mean you can't go low, but you should take your time to get acquainted with your body's new preferred style of squatting, especially if you're returning to training after injury.

4. Ankle Mobility

Stiff ankles make it tough to squat to parallel or below without your heels popping off the ground (a common squat mistake). The good news: You can improve ankle mobility by regularly including ankle drills and calf stretches in your warm-up.

5. Footwear

Wearing weightlifting shoes — which have a slightly elevated heel — reduces some of the demands on your ankle mobility, making it easier to squat deeper with an upright posture, according to a small April 2017 study in the Journal of Sports Sciences. If you don't have weightlifting shoes, you can achieve a similar effect by elevating your heels on small weight plates.

6. Core Strength

Your core acts as a bridge to connect your legs to your upper body (which typically holds the weight while you squat). If your core is weak, it's hard to stay upright as you squat. Your nervous system can even put the brakes on your mobility to prevent you from moving into what it perceives as a risky position. Learning to properly use your core while squatting can help you unlock a deeper bottom position.

7. Squat Variation and Loading Position

Front-loaded squat variations force you to stay more upright compared to back-loaded squats. This can help increase your squat depth without compromising form. This happens because holding a weight in the front of your body automatically turns on your core muscles. A front-loaded position also alters your center of gravity, so you need to stay tall throughout the rep if you don't want to fall forward!

8. Recovery Status

It's essential to give your tissues time to recover and adapt when first introducing deep squats, Oberlin says. "A deeper-than-you're-used-to squat is placing different levels of strain on different tissues. If we don't allow those tissues to adapt before we progress, they can cause discomfort or pain," he says.

Lack of sleep, poor nutrition and other factors outside the gym can affect your ability to squat deep safely.

7 Ways to Work Toward a Deeper Squat

Determined to work toward a deeper squat? "Often, with a few tweaks like lifting the heels, reducing the weight or making it an assisted exercise, anyone can hit a beautiful, full depth squat," Oberlin says.

Here are a few strategies you can use:

- Reduce the load. Sometimes, people can't squat very deep because they try to use too much weight. You may be surprised how low you can squat when you practice with less weight.

- Improve your hip and ankle mobility. Perform a dynamic warm-up targeting the hips and ankles before your squat workouts. You can also include mobility drills and stretches in between sets of squats.

- Elevate your heels slightly. Try placing your heels on small weight plates while keeping your toes on the ground. You can also squat in shoes with a slight heel such as weightlifting shoes.

- Build a stronger core. Exercises like dead bugs, moving planks and anti-rotation presses teach you to maintain tension and stiffness in your core while your limbs are moving. This is precisely the kind of core strength you need to maintain an upright torso while deep squatting.

- Use box squats. Box squats — where you squat down and tap a box or bench with your butt — provide physical context for how deep you should be squatting. Use a box placed at the exact depth you're trying to hit. This is helpful for folks who need to squat deeper as well as those who need to learn to squat a little bit higher.

- Change your loading position. Holding a weight in front of your body as opposed to on your back (eg. dumbbell goblet squat versus barbell back squat) often allows you to squat to a lower depth.

- Record your sets. Watch for form compensations and monitor your progress over time by video recording your squat sets. Using a camera allows you to keep your head facing straight ahead so you don't tweak your neck trying to look sideways in the mirror.

- European Journal of Applied Physiology: "Effects of squat training with different depths on lower limb muscle volumes"

- Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research: "Muscle Activation Differs Between Partial and Full Back Squat Exercise With External Load Equated"

- European Journal of Applied Physiology: "Effect of range of motion in heavy load squatting on muscle and tendon adaptations"

- Journal of Sports Sciences: "The effect of weightlifting shoes on the kinetics and kinematics of the back squat"